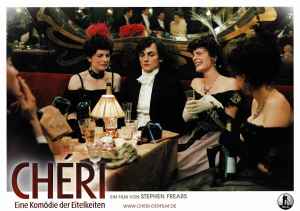

Chéri

Production Notes

Paris, 1906. By the turn of the 20th century, Paris had enjoyed several years as the most fashionable city in Europe. Its artists and writers were world famous, it was at the forefront of cultural and intellectual progress and it was the destination of choice for the world’s richest and most powerful people. It was also, of course, famous for its courtesans, women so beautiful, witty and expert in the art of love-making that Crown Princes, Grand Dukes and captains of industry from all over Europe competed for their favours – favours that came at a price.

One of the most successful is Léa de Lonval, who has become a rich woman thanks to her smart financial sense. Now in her 40s, but still a beautiful woman, she lives in an elegant Art Nouveau house where she enjoys her wealth and well-earned independence.

One day Léa goes to lunch with her old friend and former colleague Mme Peloux. Once a great beauty, Mme Peloux is keenly aware that she has lost her looks with the passing of time and this has made her a bitter and spiteful middle-aged woman. Léa has no great affection for her but knows that women of their profession have few friends in whom to confide.

Mme Peloux’s son is Fred, nicknamed Chéri by Léa, a gorgeous but spoilt young man of 19 who is living a life of louche hedonism. Mme Peloux knows he needs to grow up and sees in Léa the perfect mentor who will instruct him in the art of living and loving and prepare him for his future. Chéri looks up to Léa almost as much as he looks down on his own mother and playfully flirts with her. But there seems to be more to their feelings than mere affection: when he kisses Léa passionately on the mouth as they talk in the conservatory after lunch, she momentarily loses her cool and he is suddenly overwhelmed.

The deal, however, is set: Léa will take Chéri in until he has become a man and is ready for marriage. And so begins the education of an indolent and unformed teenager by a worldly older woman, both certain that they have built robust defence mechanisms against becoming too emotionally involved.

It was meant to last just weeks but six years has passed and Chéri is still in Léa’s house. The couple are very comfortable together, gently teasing each other, bickering good-naturedly and still luxuriating in each other’s arms. But when Chéri is summoned to lunch with his mother, her acquaintance Marie-Laure, another courtesan, and Marie-Laure’s teenage daughter Edmée, they are both surprised that Léa has only been invited to join them for tea.

When Léa arrives after lunch, Mme Peloux tells her that she is arranging a marriage for Chéri. Léa successfully conceals her shock but the news chills her. She realises it is Edmée who is the lucky bride-to-be and that the deal has been hatched between Mme Peloux and Marie-Laure, all too keen to be rid of her daughter so she can be free to work. The wedding is set for a few weeks’ time.

The same evening, Léa confronts Chéri about the news, smarting at the fact that he’d known about it for months and been too cowardly to break it to her. Her seemingly casual exterior hides a very real anger and hurt. Chéri is hurt too, and his concern is for Léa’s future: what is she going to do now? He wants to be the last young man in her life but knows that she is unlikely to change her ways.

It’s dawning on both of them that the marriage will mean the end of their relationship. Although Chéri wants to continue to be a part of Léa’s life, she knows that her time is over and she must banish him from her life. The realisation cuts them both to the bone.

During their honeymoon in Italy, Chéri’s anger and frustration comes to the fore and his emotional cruelty towards his innocent young bride is shocking. Meanwhile back in Paris, Léa has to endure the barbed comments of Mme Peloux who takes great pleasure in seeing her rival so emotionally vulnerable. She decides to escape to Biarritz and leads Mme Peloux to believe she’s in the company of a new man. Indeed, when she arrives on the coast, she meets a young man named Roland who enthusiastically enjoys her favours.

When Chéri and Edmée return, it’s clear the honeymoon has not brought them closer together. And it’s clear that Chéri is still pining for Léa. Very soon, it becomes too much for Edmée and she snaps, reproaching her husband for his indifference and cruelty. Chéri can bear it no longer and later that night leaves the house. He moves into the Hotel Regina and spends his days partly staking out Léa’s villa awaiting her return and partly killing time in an opium den run by a former courtesan, La Copine.

Three weeks later, Léa is back in Paris and Chéri returns overjoyed to his mother’s house and into Edmée’s arms – at last, the waiting is over! Mme Peloux visits Léa and the mention of Chéri’s name send a shiver of melancholy yearning through her – which Mme Peloux, in all her spite, enjoys provoking.

Later that night, Léa is confronted by Chéri who sweeps into her boudoir announcing his return. Léa is overjoyed at his return and the pair collapse into each other’s arms. The next morning she begins to make arrangements for their departure – to the South, perhaps, somewhere far away where they’ll cause as little scandal as possible – but Chéri is strangely quiet. He wasn’t expecting this, he wanted to keep Lea in Paris as a distraction from his life with Edmée. At least with Edmée he can be a man, he thinks; with Léa, he’ll always be a boy.

It’s too much for Léa. After a tearful embrace, she makes the ultimate sacrifice and forces him to leave. As she watches him walk away, she begins to contemplate a life without him.

Amount The Production

Christopher Hampton, the Academy Award-winning screenwriter behind Dangerous Liaisons, was developing a screenplay about the renowned French author Colette (1873-1954) when he began adapting her most famous novel Chéri. Written in 1920, it told the story of the doomed love affair between Léa de Lonval, one of the most celebrated courtesans of the day, and Chéri, the young son of an old colleague and rival.

“Colette has always been one of my favourite writers and I got very interested in doing the Colette life story because she had a tyranical older husband and ran away to become a striptease artiste,” says Hampton. “Colette is loved and admired because she writes in a very individual and personal way and writes very sensitively about women. With some writers you don’t need to research much but Colette was fascinating and it was a pleasure to read her other works.”

It was the love story theme of Chéri that proved such an irresistible attraction for Hampton. “It’s a story of two people who have no idea that they’re in love with each other,” he says of the film’s protagonists. “Léa thinks she’ll educate this younger boy and then pass him on a wiser man, and Chéri thinks he’s landed on his feet with a beautiful woman taking care of him until it’s time for him to move on. They know there’s an end point to their relationship. But when it arrives they both realise that they will miss each other very badly. A rather heroic act by Léa liberates Chéri and lets him go but at great cost to herself. You suspect he won’t recover too well either.”

Of course, the early 1900s milieu in which the story is set was another draw for the writer. “This is a fascinating world, this demi-monde, which at the end of 19th century reached its peak but was approaching its decline at time of the story in 1906,” says Hampton. “This was a corner of society, the courtesans, who had amassed spectacular wealth. They had to stick together because they were shunned from the rest of society but they had very interesting lives, they were very cultivated and they were unlike any contemporary group you can think of. There was something very modern about this group in one respect because they were emancipated women.”

Although translating from the original French afforded Hampton a certain freedom in being able to pick and chose from the dialogue in the novel, the fact that it isn’t a conventional narrative posed a more taxing creative challenge. “Colette’s an impressionist, there are little bursts of dialogue or imagery,” he explains. “She can spend 20 pages on one scene but three months can fly by in a paragraph. At the start I found I had a first draft that was longer than the novel itself! So I had to ruthlessly prune.”

After various false starts, Hampton discovered that Bill Kenwright, top UK theatre impresario, had optioned the rights, just as Kenwright himself was about to approach Hampton to tackle his long-gestating screen adaptation.

“Christopher Hampton was my first choice to adapt the novel,” says Kenwright. “His first draft was wonderful but it was a real battle to get it onto the screen because it’s a costume drama, because it’s such a simple, focused story, because it’s so tragic and I would have thought mostly because the world of the Courtesan is probably not one that contemporary audiences know a lot about.”

It was Stephen Frears’ involvement that finally brought the project together at the end of 2007. The director was riding high thanks to The Queen which not only won lead Helen Mirren an Academy Award for Best Actress but also became a worldwide hit for Miramax. He was approached by Kenwright and agreed to come on board within 24 hours of reading the screenplay.

Frears was attracted to the project partly because of Hampton’s evocative screenplay but also because it was a chance to explore an era some 100 years removed from The Queen.

“Christopher’s script was wonderful and Colette is a brilliant writer and the story seemed very fresh to me,” says the director. “It’s so beautiful, so old-fashioned and so frivolous and yet also so melancholic and tragic, and at the same time very clever. That’s because Colette was such a clever writer. She’s an impressionist. The story is a series of impressions and making them all add up into something is the challenge. It’s the most extreme film I’ve ever made and the most original story about people living in a bubble. These women were very powerful and had a lot of influence, but they lived in an enclosed society which was cut off from the mainstream. And as Lea tells Madame Peloux, they have to make friends within the profession because no one else understands them. And, of course, they’re also acutely aware of what happens to them when they age and lose their beauty”

For a director who says he finds making films “very difficult”, he won the admiration of the whole cast and crew. Says Hampton: “I like working with him very much. I soon learnt that it was very unusual for a director to have the writer there – it’s too dangerous to have a boring pedant there all the time picking holes in what’s going on – but Stephen’s different. There’s an enormous depth and generosity to his collaborativeness. He has a very subtle approach when a scene isn’t working, when a scene is too long, or something doesn’t work. I’ve learned to trust those instincts. It’s often to do with words but also to do with concision and often to do with mood, finding a pause that will complete the music of the scene. In that sense, he’s very intuitive.”

Frears also lived up to all Bill Kenwright’s expectations. “I was huge fan of Stephen’s – two of my favourite films are The Grifters and Hi-Lo Country – and it was a thrill to work with him. You’re blessed when you find someone like Stephen; I knew he could make the film work. And he’s great with the actors; he does a lot of takes, to get the actors’ juices going. He knew exactly what he wanted and how the film should look from very early on. He was very painstaking and focused and was meticulous about the mood of the film. Really, he’s a master.”

With Frears at the helm, Kenwright was able to secure backing from two key partners, Pathe and Miramax Films. But the key to making the film succeed was finding the right actors for the roles of Léa de Lonval and Chéri.

Casting The Film

Casting the character of Léa proved a unique challenge. The filmmakers knew there were few actresses who had the qualities they were looking for as a woman in her 40s who was naturally beautiful and sensually charismatic. One name, however, was the perfect fit and she had already worked with Frears and Hampton – Michelle Pfeiffer, whose haunting performance in Dangerous Liaisons won her her first Academy Award nomination in 1989 and had recently returned to the spotlight with acclaimed turns in Stardust and Hairspray.

“Pfeiffer,” says Frears with characteristic insight “upsets you. She was upsetting in Dangerous Liaisons – I knew that as soon as I met her – and she’s upsetting in this. She’s unnerving, as though being that beautiful contains its own tragic quality.”

But it was not just her mesmerising screen presence and looks that made her ideal for the part. Her performance captures exactly the spirit of the novel. As producer Bill Kenwright says, “Michelle took a chance doing this. The character could be played in several ways but Michelle’s subtlety and vulnerability is astonishing.”

For her part, Michelle Pfeiffer required very little persuading to board the project. “It was the thought of working again with Stephen and Christopher that appealed so much,” says Pfeiffer. “Really, I’d do anything with Stephen and when I read the script and the novel, I was thrilled to be involved.”

“What I like about Colette’s writing is that Léa is not a cartoon version of what a courtesan of the time would look and behave like,” continues Pfeiffer. “She’s smart, she has a great sense of humour and she’s kind. She’s classy and elegant and she’s also a good person and that’s very unexpected. She’s very happy with her life – the top courtesans like Léa were independently wealthy and very smart businesswomen and travelled among the aristocracy – but then this young beautiful boy Chéri comes into her life and she loses her perspective and falls prey to her heart for the first time in her life. I think she regrets that love has never happened for her but she’s always accepted it happened because of the choices she has made. Perhaps she feels that this was her last chance. We see her grapple with the aging process – she’s over 40 after all – and towards the end of their relationship she can’t deny that she’s getting older and we see her coming to terms with and accepting that.”

Working with Christopher Hampton also proved a powerful draw. “Christopher’s writing is so beautiful – but it’s also unbelievably challenging particularly for Americans. We talk in a flat monotone and Christopher’s writing is dense and wordy and has a very different rhythm to it. I found that breaking it down into iambic really helped in getting the rhythm and cadence right. That Christopher was on set all through the shoot was so comforting for me – Colette’s writing can often be open to interpretation so it was a boon to have him there to discuss the characters’ motivations and thought processes.”

One challenge of the film was Frears’ working methods. “We didn’t rehearse,” she laughs. “We would only rehearse on the day of shooting so it was a really tough process but it’s the way Stephen worked. It got really difficult when the script changed at last minute. You know, I’d spend a long time learning the lines and the rhythm of those lines and then they’d change it right when we got on set! By the end of the shoot, I’d started sending them very polite texts saying, ‘Yes, of course, I know you need to rewrite but could we please have a little more notice!’ But really, working with Stephen was a treat. He’s such a lovely character – he walks around he set like a grumpy old man but he’s funny and smart and it was a joy to work with a director of his calibre.”

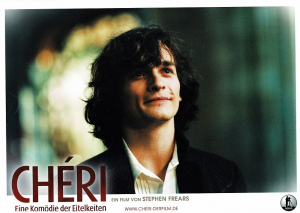

The role of Chéri was another challenge. The filmmakers were looking for an actor who could convincingly look 19 years old at the beginning of the film and who could imbue the role of a spoilt, selfish young man with a quality audiences could sympathise with.

Frears auditioned several American actors but it was British newcomer Rupert Friend who convinced as a young man at once virile but sensitive, cocky but vulnerable, a young boy who gradually matures into a man who realises how much his older lover has come to mean to him. He thus becomes another of the long line of budding actors on whom Frears has taken a punt and who have gone on to international stardom, including Chiwetel Ejiofor (Dirty Pretty Things), Michael Sheen (The Deal), Jack Black (High Fidelity) and Daniel Day-Lewis (My Beautiful Laundrette).

“Chéri is 19 years old when the story stars,” says Friend, “and is carefree, spoilt and untroubled but he’s a callow young man and his mother knows that he needs to learn the qualities that will help him get on – refinement, conversation, etiquette. And Léa has many years of experience and can teach him and not pander to his selfishness. But the relationship changes after six years when Léa finds out about his arranged marriage to Edmée. She feels betrayed when she finds out. And Chéri can’t decide where he wants to be – with Léa or in a conventional marriage which will give him an air of respectability.”

Finding the key to the character provided its own challenges for Friend. “There’s something elusive about Chéri,” he explains. “And there’s also a sense of enormous apathy about him; he’s very passive. That makes it very hard: if you’re trying to find what’s driving someone and the answer is nothing, it makes it much harder to get a handle on the character – harder, but very rewarding when you find it.”

Friend returned to Colette’s original novel when he needed inspiration. “Colette is such a great writer,” says Friend, “She manages to convey something in just one sentence, picking out the one detail you need to see the whole character or the whole scene.”

As for working with such a formidable line-up of talent, Friend says: “I’d be lying if I didn’t say it was quite frightening acting with Michelle Pfeiffer and Kathy Bates but once the work started they became Madame Peloux and Léa. I had to think of them like that or I wouldn’t get out of bed every morning for shaking! But when you work with actors of that calibre, you’re galvanised into raising your game. And they were so professional and so generous with me.”

If he was intimidated, then Friend certainly didn’t show it. “Rupert is so young but so very smart,” says Pfeiffer. “He was a gentleman all through the shoot, especially during the more challenging scenes, and if he was nervous, he hid it very well.”

Working with Stephen Frears also proved a particular pleasure, he says. “Stephen was perfect for Colette because both have an incredible wit and a love of dry humour. They’re both always looking for a wry angle. Colette paints a world where people are caustic about each other but are fond of each other too. But it’s a world of verbal jousting and where things change in a heartbeat; it’s mercurial. And that’s Stephen too.”

For the role of Chéri’s mother, the filmmakers approached Kathy Bates. The Academy Award-winning actress jumped at the chance to portray the larger-than-life Madame Peloux who has become bitter in middle-age but still remains a comic character because of her catty bitchiness.

Says Stephen Frears: “As soon as Kathy’s name came up, I knew she had the humour to do it. Filmmaking is about assembling a group of people who fit together; you’re trying to get the picture right, so everyone is making the same film. And I knew Kathy would fit.”

It was not just the character of Madame Peloux and the chance to immerse herself in the period that proved such a powerful draw for Bates. It was also working with Stephen Frears

“These courtesans had become very powerful, influential and rich,” she says. “The story is set towards the end of their heyday and, like many of her peers, Madame Peloux is no longer working and so is very money-conscious. She knows she has no way of making a living now except by being smart over her money. It has made her manipulative; she manipulates everything and everyone to her own satisfaction. She uses Léa, with whom she’s always had a fierce rivalry, and her own son to gets what she wants, which is money.”

As Michelle Pfeiffer explains, the relationship between Léa and Madame Peloux is borne more out of necessity than any genuine affection. “However independent these women were, they were also isolated and were inevitably judged by the rest of society. So there’s a kinship between Léa and Mme Peloux because they understand each other’s worlds and what it means to be a courtesan. It’s like any profession – only people who belong to the same profession can truly sympathise with each other. But there’s also a competitive edge to their relationship – probably in the past over men but even now over Chéri. Madame Peloux may have manipulated the entire thing – she wants someone else to take care of her out-of-control son and shoulder the financial burden of looking after him – but I suspect there’s an underlying rivalry over him.”

“Madame Peloux was not a good mother,” continues the actress. “Courtesans in general didn’t like the idea of children because they marked their age. Often they would go off for a year or two with this archduke or that prince and their children were left in the care of friends or servants. So Chéri would have had a very lonely and disjointed childhood. He has drifted a lot, he doesn’t really have any roots and he wouldn’t have known who his father was. I saw him as a bit savage with no allegiances to anyone; a bit of a wild child. He has his freedom but he doesn’t know what to do with it.

“Madame Peloux is worried about him because he’s young and wasting himself in drink and he’s costing her a lot of money. So that’s why she has arranged to pawn him off on Léa so that she can teach him the ways of the world and also pay for his upkeep. It will keep him out of trouble and makes him marriageable and that will confer respectability on him.”

Of course marrying him off means a dowry. “She may give Léa a line about wanting grandchildren but it’s really all about money so she will be comfortable in her dotage even though she wants him to be married, respectable, in love and rich – all the things that were unavailable to her as a young woman of her profession.”

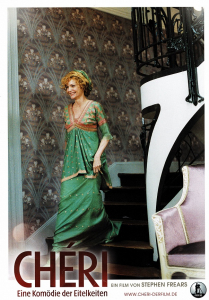

Unlike Léa de Lonval, who has the self-confidence to look towards the future and embraces the novelty of modernity beginning to influence French culture and society, Madame Peloux is still lodged firmly in the past. Unable to come to terms with her faded beauty, she overcompensates by surrounding herself with gaudy clutter that ostentatiously show off her wealth. “Her house is a museum of all the gifts she’s been given over the years, trophies of her lovers,” explains Bates.

It was not just the character of Madame Peloux and the chance to immerse herself in the period that proved such a powerful draw for Bates. It was also working with Stephen Frears.

“I was over the moon when I heard that Stephen would be directing this,” she says. “I had no rehearsal time on this film: the morning I arrived I went for costume fittings and the next day we were shooting! I was really thrown in at the deep end. I like rehearsal and preparing and here I didn’t have a feel for the era or how to move in the clothes. So I really had to trust Stephen to tell me if I had the right tone. But he was right there all the time, just underneath the camera, and he was like a conductor. All I can say is that he’s very unassuming, a lovely, very funny, self-deprecating, unique man. He brought class, intellect, wit and humour – that wry, dry British humour – to the piece. He was so much fun to work and that’s what I get to take away from the set.”

Rounding out the cast are Felicity Jones as Edmée, Chéri’s young wife who pragmatically decides to make a success of her marriage and finds in Chéri someone who understands her background; Iben Hjejle as Edmée’s cold-hearted courtesan mother Marie-Laure; and Anita Pallenberg as a former courtesan and madame of an opium den.

With the cast in place and the final pieces of the financing jigsaw provided by by Aramid Entertainment, Germany’s NRW Filmstiftung and the UK Film Council’s Premiere Fund, the film began shooting in April in Paris and Biarritz before moving to Germany’s MMC Coloneum Studios for interiors. With Tracey Seaward and Andras Hamori on board as producers, the highly acclaimed crew included cinematographer Darius Khondji (Funny Games, Se7en), composer Alexandre Desplat (The Queen, Lust, Caution, Syriana), production designer Alan MacDonald (The Queen, Kinky Boots), costume designer Consolata Boyle (The Queen), hair and make-up designer Daniel Phillips (The Queen, The Edge of Love) and editor Lucia Zucchetti (The Queen).

Recreating The Period

One of the most generous directors when it comes to collaborating with his creative heads of department, Stephen Frears insists he relies entirely on his cinematographer and production and costume designers for how the film will look. Those who worked with him, however, know just how crucial his input was in the making of CHÉRI. Says composer Alexandre Desplat: “He says he knows nothing about the music or the design? He’s lying! Stephen has a great intuition of what the movie is aiming for and he knows exactly what will work when they’re put together. With the music, for example, he doesn’t ask me to change this chord or that note, but he says make it nastier or wilder or give it more wit. And he’s very involved.”

CHÉRI marks award-winning cinematographer Darius Khondji’s first collaboration with Frears. “Stephen is a very visual director,” says Khondji. “He has a feel of what’s right and wrong for the mood but unlike other directors he doesn’t talk about angles and camera positions. With Stephen what comes across much more clearly is the mood that the film should take.”

“We talked about the period, the mood, the atmosphere, the look,” he continues. “Our discussions embraced the work of Max Ophuls, Jean Renoir and Bertolucci’s The Conformist even though not same period as well as impressionist paintings. Colette is, after all, an impressionist writer in a way. But I never try to mimic paintings, there just has to be a subliminal reference to art, it has to haunt the mood.”

The setting of the film – 1906 when Europe was on the brink of moving into modernity – also informed Khondki’s approach. “Madame Peloux is stuck in the past whereas Léa looks forward and this contrast between their characters inspired the lighting. At Léa’s house, the camera is luminous, light and mobile, and free. But when we go to Madame Peloux’s home which is dark and oppressive and crammed with expensive but vulgar objects, the camera is static and heavy.”

Working on the film brought some surprising rewards for the cinematographer. “I didn’t know I loved shooting in Paris!” says Khondji. “Maybe it was the period setting, maybe it was Stephen’s approach, but this film was much more exciting to be involved with than others I’ve worked on.”

Alan MacDonald, who worked with Frears on The Queen, was brought on board as production designer. He plunged himself into researching the period around 1906 when the film is set and it was this that provided inspiration for the contrasting looks of Léa’s and Madame Peloux’s worlds.

“I realised that we were dealing with a time of innovation,” says MacDonald. “We think of ourself as innovators, but 100 years ago society was going through seismic changes with the proliferation of train travel, electricity, photography, cars and the telephone to name just a few innovations of the era. Madame Peloux was living through this but I saw her as living in the past, she knows what suited her and she would stay with it for ever. Léa understands the changes sweeping through society.”

Using photography as his reference for Léa’s home and impressionists, post-impressionists and symbolist painting as his reference for Madame Peloux’s house, MacDonald created the two contrasting looks of the film. Where the acquisitive Madame Peloux’s house is stuffed full of opulent, mismatched furniture and gawdy bricolage and objects d’art from the 19th century and before, Léa’s airy, elegant house reflects her exquisite taste for modern art and design.

The interior of Madame Peloux’s house, which was filmed at a chateau 20 km outside Paris, is crammed with items sourced from Parisian antique shops and props houses including stuffed birds and animal heads, velvet drapes, animal skins, gilded candelabras and vases, heavily ornate clocks and timepieces, marble tables, embroidered carpets and blankets and heavy crystal decanters. Everything smacks of someone with too much money and too little taste.

“There’s also a portrait of Madame Peloux as younger woman,” says MacDonald, “and it shows what a great beauty she was but it’s now a shrine to her youth and a reminder to the audience of the power her beauty represented.”

Léa’s home could not be more different. MacDonald and his team were fortunate to have as their main location the villa designed and owned by Hector Guimard, the architect who designed the iconic art nouveau entrances to the stations of the Paris Metro.

“Léa has moved with the times,” explains MacDonald, “she has embraced the modernity of art nouveau. Where Madame Peloux’s house looks enormous from outside but has tiny rooms, Léa’s has a more open-plan, fluid feel with large, spacious rooms. Maison Guimard was one of first houses with central heating, so there are no fireplaces which allowed architects to open up rooms and allows light to lead from one room to the next through french doors.”

The design of the room reflects Léa’s love of modernity. Rather than paintings adorning the walls, MacDonald used wall paper – reproduced from original contemporary designs and in calming pastel colours of lilacs, greys and blues – and the occasional understated wall decoration. Because Léa has been freed from the constraints of the tight corset and bustle, the furniture is more relaxed with simple shapes and elegant lines. MacDonald also used plants and flowers to decorate the interiors, reflecting a contrast with the dead animals in Madame Peloux’s mansion.

Léa’s boudoir, where so much of the film is set, was recreated at the MMC Coloneum Studios in Germany, where MacDonald designed the beautiful art nouveau bed.

Locations also included the Hotel du Palais in Biarritz, where Léa escapes, and in Paris the Hotel Regina, Saint Etienne du Mont, the church where Chéri and Edmée get married, and the legendary Maxim’s restaurant which doubled for the Restaurant Dragon Bleu, where Chéri spends his evenings with his best friend Vicomte Desmond.

Costume Designer Consolata Boyle also took her cue from the contrast between the two female protagonists of the film. “There’s a simplicity to Léa’s look,” says the designer, “and the cool, empty space of her home shows her confidence. She’s a woman of wonderful taste and not encumbered by things. She has it all but doesn’t have to flaunt it. Peloux, meanwhile, sees things as a sign of her success and status. “

Inspired by her research into impressionist painting, Boyle designed all the costumes for the main characters. While Madame Peloux’s gowns are heavy, dark and richly embroidered and she wears big, showy hats, Léa’s style is unfussy and cooler and shows off the clarity and beauty of her silhouette.

Boyle worked closed with hair and make-up designer Daniel Phillips whose research underlined the fashion for hats during the period. The soft hairstyles of the period were exaggerated for Madame Peloux while he went for a prettier, more subdued style for Léa inspired by the paintings of Gustav Klimt.

For the elusive Chéri, meanwhile, Boyle took her inspiration not only from his physical beauty but from the world of ballet, music, theatre and culture that Léa introduces him to. “The type of young man in Paris at that time had an obsession with clothes, with finishing and fabrics, and they were very sophisticated. In essence, he’s a dandy.”

The final element of the film was provided by composer Alexandre Desplat, whose score for The Queen won him an Academy Award for Best Music. He took his inspiration from the music of the early 20th century in France – a fruitful period which saw the rise of Saint-Saëns, Debussy and Ravel – as well as the Orientalism and mysticism that was informing art and culture at the time, Desplat created a score that combines the refinement of French composition with the exoticism of Chinese violins.

“The best score brings out the emotions that aren’t obvious on the screen,” explains Desplat. “The character of Chéri is melancholic, sensitive and closed off and he doesn’t know about life, he goes with the flow and is not very active except sexually, of course. The music has to bring out the sensuality to the film – after all, it’s about a boy of 19 who knows little but has considerable sexual power and a woman in her 40s who’s an expert in sexual matters.

“It’s an intimate film too,” he continues, “so the orchestra can’t be too intrusive. I used a small orchestra of 50-70 musicians and half the score is just strings and I brought in a string trio with the viola as lead playing on a higher register which gives it a darker sound.”

It was not just the screenplay that inspired Desplat. He was moved by the interplay between the film’s two leads. “Michelle Pfeiffer and Rupert Friend have a very strong chemistry,” he says, “and I wouldn’t have been able to write the score without the subtlety and emotion of their acting.”

The Courtesans – A Brief Guide

Known as the grandes horizontales, courtesans in late 19th century Paris were the height of fashion.

Renowned throughout the world for their beauty, wit, conversation and skill, these demi-mondaines were at the centre of Parisian social and political life, entertaining the most powerful men in government, royalty and the arts, but remaining cut off from the mainstream in an exclusive closed-off world.

They influenced fashion, lived ostentatious life styles that showed off the wealth of their lovers and were hotly in demand among the richest of Europe’s aristocracy who would compete to enjoy their favours.

Of course, those favours did not come cheap and the most famous courtesans amassed vast wealth through sensible investments and judicious acqusitions of property and assets. Personality and beauty were their only commodities and the shrewdest knew that their status would only last as long as their looks.

Among the most famous courtesans of the time were Apollonie Sabatier whose salon welcomed intellectuals such as Baudelaire and Flaubert, Marie Duplessis who was immortalised in Alexandre Dumas fils play La Dame Aux Camélias, Esther Pauline Lachmann who became known as La Paiva and married Count Henckel von Donnersmark, and English-born Cora Pearl whose lovers included Prince Napoleon.