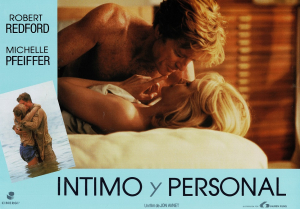

Up Close & Personal

“UP CLOSE & PERSONAL”

Production Information

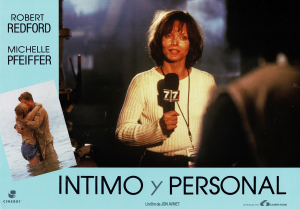

Tally Atwater (MICHELLE PFEIFFER) is one of the most trusted figures in the nation. A familiar and comforting face to the millions of network TV news viewers who invite her into their homes every day, Tally is an articulate, sophisticated and

charming newscaster. But she didn’t start out that way. A onetime waitress and casino craps dealer named Sallyanne, from Reno, Nevada, she pursued a dream with nothing but ambition, raw talent and a homemade demo tape.

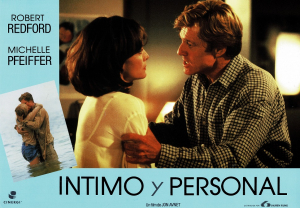

Going from a small-town weather girl to prime-time network anchor, her meteoric rise to prominence is aided and abetted by Warren Justice (ROBERT REDFORD), a brilliant, older newsman who becomes her mentor and lover. As their relationship grows, so too does Tally’s celebrity, to the point where her popularity begins to eclipse Warren’s. Justice, a hard-edged, veteran newsman, still stubbornly believes that substance matters in a medium increasingly infatuated with style. Under his

tutelage, the inexperienced Sallyanne becomes the admired Tally Atwater, lovedby the camera, by the audiences who watch her and, slowly, much to his surprise, by the man who invented her. The romance that results is as intense, exhilarating

and revealing as television news itself. Yet, each breaking story, every videotaped crisis that brings them together also threatens to drive them apart, in Touchstone Pictures’ romantic drama, “Up Close & Personal.”

Touchstone Pictures presents in association with Cinergi Pictures Entertainment, An Avnet/Kerner production, A Jon Avnet Film, “Up Close & Personal.” Directed by Jon Avnet, produced by Jon Avnet, David Nicksay and Jordan Kerner, written by Joan Didion & John Gregory Dunne, suggested by the book “Golden Girl” by Alanna Nash, the executive producers are Ed Hookstratten and John Foreman. Co-producers are Lisa Lindstrom and Martin Huberty. Buena Vista Pictures distributes.

Filmmaker Jon Avnet, who has helnned such critical and boxoff ice successes as “Risky Business,” which he produced, and “Fried Green Tomatoes,” which he produced and directed, was attracted to the elements of romance and the media and how they impact each other in “Up Close & Personal.”

“I’ve always been interested in the media, so that aspect of the story was appealing,” producer/director Avnet says. “I also thought that the exploration of a contemporary romance could be challenging as it is so difficult to find classic obstacles to keep people apart anymore. There are no more Montagues and Capulets, nor are there rigid, absolute societal mores, but in ‘Up Close & Personal,’ the relationship between the two principal characters becomes the obstacle. This is a mentor-protégé relationship in which the protégé ultimately reawakens the mentor to what and who he was. That was very attractive to me.”

For 1980 Academy Award® winner Robert Redford the opportunity to star in “Up Close & Personal” was more about the film’s love story than its backdrop against the news media. “What interested me the most was the fact that it was a good, tough, love story about two people on the raw edge of life, drawn to each other on dangerous terrain,” Redford says.

Different from other characters he has portrayed on screen in the recent past, the role of Warren Justice offered Redford an attractive change of pace. He describes Warren as “a tough, uncompromising character, and therefore a difficult man. But difficult people are very often fun to play. His flaws were interesting to me, because they had to do with the dangerous edge that he lives on, the rawness and purity of his character. He is uncompromising. Those are all interesting character points.”

For two-time Academy Award® nominee Michelle Pfeiffer, accepting the role of Tally Atwater was an opportunity to create a multi-dimensional character in a contemporary love story. “Even though she’s very ambitious, there’s an honesty to Tally and her ambition,” the beautiful and talented Pfeiffer says. “But she’s not ruthless in her climb to the top of her profession. She may be from a trailer park, but she has a lot of integrity. She’s very complicated.”

The idea of working with screenwriters Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, was enormously appealing to producer Avnet. “They are great writers, who write, rather than talk fora living. They are smart. And they know the world of the media inside and out.”

Robert Redford agrees, adding, “They represent a very tough, true and almost poetic mind to the social condition that we live in. I’ve always liked that about them. They’re both talented, and talented in slightly different ways. They look at things a little bit the way I do — with a kind of squinty eye for where the truth is. And then they write it in a colorful way — but always with the truth.”

When Avnet was asked “VVhat relationship this movie bears to the Jessica Savitch story?” He answered, “Very little.” He continued, “I was offered a script by Joan and John about a contemporary romance in the news world, about four years ago. I was not offered a period story about the rise and tragic fall of Jessica Savitch. I had no interest in doing a period piece about the media and was not interested at this time in my life of doing a story about a woman self-destructing on her way to the top. One of the elements that did appeal to me in Joan and John’s script was that it wasn’t a media bashing story. Ultimately, what we wanted to do was get some insight into that world and how it affects the people within it. We were interested in its effects on a personal level, which can be so subtle, in contrast to the repercussions of the media on a cultural level, which can be so grandiose.”

A film so tied to the shifting nuances of the professional and personal relationship of its protagonists required actors of the highest caliber, dynamic talents who would capture the character’s undeniable passion for each other and for the TV news business.

The pairing of Redford and Pfeiffer were on the money for Avnet. “They generate real chemistry.” He notes that both actors bring a lot to the table. They both can carry movies on their own. They both immersed themselves in the world of television journalism. “I took Michelle and Bob separately to local and network stations to observe every detail of creating a newscast, to the point of taping both of them at anchor desks reading the TelePrompTer. They each interviewed numerous people in front of and behind the camera.” Avnet adds, “They really made the effort to get it right.”

In addition to watching tapes of real-life newscasters in action, Michelle Pfeiffer’s homework included interviewing numerous respected journalists in the industry. “It’s not as glamorous as I thought it might be,” Pfeiffer says of the behind- the-scenes world into which she delved for research. “I have a lot of admiration for these people because I realize they do a very difficult job.”

The pivotal part of Ned, Tally Atwater’s loyal cameraman, went to Glenn Plummer, with whom Avnet had previously worked on the award winning TNT movie about the Watts Riots called “Heat Wave.” Aside from Warren Justice, Ned is the only character who follows Tally through all her professional incarnations, serving as her partner and confidante.

“In all the movies he’s done, he’s always brought something unique, unexpected and interesting to the role. He came in and read for us and just blew everyone away,” Avnet remembers.

Plummer, in turn, was eager to work with Avnet again. “Jon is great, he’s very physical, he loves to get in the mix, to bump it and move it around. There is an old saying that talent does what it can, genius does what it must. Jon creates situations where people do what they must, not what they can.”

Joe Mantegna, who plays agent Bucky Terranova, won the role without even trying. Mantegna came to the first reading of the script as a favor to casting director David Rubin and his interpretation of the part, even in a read-through, convinced

Avnet that he had found his Bucky Terranova. Mantegna describes Terranova as “fun to play, a little flamboyant with his own sense of style, but a guy who genuinely cares about his clients.”

Admirers of Stockard Channing’s work, especially her Oscar-nominated portrayal of the wealthy, refined Manhattan socialite Ouisa in “Six Degrees of Separation,” the filmmakers thought she would make an outstanding Marcia McGrath, a cool, poised newscaster who becomes Atwater’s professional rival.

Casting the part of Joanna Kennelly, Warren Justice’s ex-wife and a famed TV journalist in her own right, proved to be an interesting exercise. The part required a performer who could embody a strong, wise, attractive woman, the archetypal television anchor who would serve as a striking counterpoint to Tally Atwater.

Many actresses vied for the role, but Kate Nelligan, whose Oscar-nominated supporting performance in “The Prince of Tides” had so impressed Avnet, finally won it.

Dedee Pfeiffer, known for her comedic appearances on the hit comedy series “Cybill,” as well as a stand-out performance in the controversial hit film “Falling Down,” was cast to play Luanne Atwater, Tally’s spirited sibling. Dedee and Michelle Pfeiffer are sisters in real life and their camaraderie and easy rapport translated directly to the screen. The Pfeiffers were not the only family represented in “Up Close & Personal.” Producer David Nicksay’s daughter Lily graced the film as Luanne’s daughter Star.

ABOUT THE PRODUCTION

“Up Close & Personal” shot on locations in Miami, Philadelphia and Los Angeles, in settings as disparate as the Orange Bowl, a Philadelphia prison and a Hollywood sound stage. Throughout the production, Avnet tried, as authentically as possible, to capture the high-pressure, fast-paced world of television news that defines and determines the characters arid events of “Up Close & Personal.” To that end, Avnet immersed himself in the unique milieu of television news prior to filming, researching for over a year and a half, visiting every network and the vast majority of local stations in New York, Miami, Philadelphia, Washington and Los Angeles, interviewing and observing every network nightly news anchor, producer, morning show host and well known pundits, along with their counterparts. Co- producer Lisa Lindstrom, who has worked with Avnet for nearly a decade, accompanied him and facilitated much of this research, likening it to a “giant treasure hunt.” Executive producer Ed Hookstratten, a renowned agent for many of the network and local newscasters, facilitated some of this treasure hunt, and, in the process, became an enormous Jon Avnet enthusiast.

“I’m a gigantic fan of Jon Avnet,” Hookstratten says. “He has a wonderful eye and knows how to execute his vision. And the homework that he did, visiting news stations all over the country, was incredibly meticulous.”

Producer David Nicksay notes that Avnet’s zealous interest in the news business is part of his appeal as a filmmaker and reflects his cinematic style.

“Jon is relentlessly curious, it’s one of the ingenuous things about him,”

Nicksay comments. “He’s never learned to turn off his sense of wonder. He’ll follow it into a new environment, explore and discover. Then, he’ll look at the moment he’s trying to create for the movie and marry it to what he’s discovered.

That’s why the research was so important. When we initially talked about a sequence, his first questions were always, ‘What’s it really like? What really happens? Show me the real thing,’ and we’d go from there.”

Hookstratten can attest to Avnet’s Trumanesque “show me” attitude. During his painstaking research, the filmmaker insisted on meeting a Warren Justice prototype. “I knew exactly who it was, though I’m not going to name him,”

Hookstratten says. “I brought this person to lunch one day and half-way through it, I saw Avnet start to grin and he said, ‘My God, this is the character.”

Part of Avnet’s fascination with the medium stemmed from what he refers to as “The Magic Box Factor.”

“When I was 5 years old, I had what I thought was the great fortune to visit a local TV show I watched with great regularity. When I walked on the set, I was stunned and disappointed by what it looked like. This great place I saw on television was just this flimsy set with these little bleachers and grown ups in bizarre costumes going in and out of character. It was clearly nothing like the world that had been created for me on TV. I thought I finally understood what my aging grandmother would say in her broken English when she called the television ‘A Magic Box.’ Similarly, there is such a difference between what you see and what really goes into making the news and what goes out on that television has such a

profound influence on our lives.”

In “Up Close & Personal,” Avnet hopes to examine television news by revealing how it is created, literally and figuratively, beginning with the first shot of the film.

“The idea is to get inside and behind this cathode ray that affects us every day. It is a love-story and it is important to realize that, but the media is the story behind the romance. In order to tell both stories, we used a lot of images that are reflections, projections, video images, which appear to be normal. In the film, you see characters in various forms of video from hi-8 to professional quality Beta and in various forms of degraded images, yet people react ‘normally’ to these images

as they appear on the magic boxes. During broadcasts, you’ll always hear the ubiquitous off-camera voices behind the scenes simultaneously. Hopefully, it creates a desire to understand and see this world behind a world, but it will also force the audience to question on some level exactly what it is seeing and or hearing.”

This dual use of video and film images complemented the film’s love story, especially during the prison riot scene, when the only way Warren Justice can see his wife and protégé, Tally Atwater, is via a fuzzy video transmission.

This blurry line between image and reality became manifest in different ways throughout the film. For instance, the camera perched on Glenn Plumnner’s shoulder was not just a prop. Plummer studied for two weeks prior to filming, learning how to use the video camera and, as Avnet filmed the scene, Plummer, as cameraman Ned Jackson, actually rolled tape of Pfeiffer as Atwater, conducting interviews, chasing stories and delivering stand-ups. Plummer’s work won high marks from the video and camera crew, and Plummer has developed a great respect for cameramen, whom he calls “the smartest guys in the news business.”

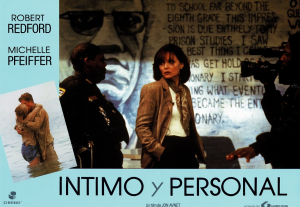

Additionally, Avnet cast working television journalists, from Miami and Philadelphia, respectively, to play the ubiquitous press corps. He also recruited area locals to play themselves. The Spanish-speaking residents who frequent the chess and domino clubs in Miami’s Little Havana appear in the background of Tally Atwater’s news stories there, while several inmates featured in Atwater’s coverage of a prison riot were actually incarcerated in Philadelphia’s Holmesburg Prison, one of the country’s oldest working correctional institutions, where the production shot some of the uprising scenes.

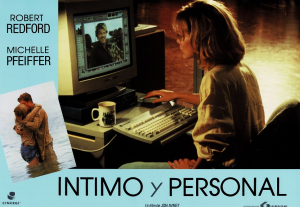

“One of the most fascinating parts of working on this film for me was this technology, how to unite video and film,” producer David Nicksay comments. “Film goes at 24 frames per second and video goes at 30 frames per second and we needed to bring those two media into sync with each other. We wanted to present the videotape image as an icon, almost a holy artifact in the news world. It’s present in the foreground, in the background, subliminally. Everywhere we could get it, we jammed it into the frame. Live images and pre-recorded taped ones, edited tapes and raw video, archival footage mixed with very fresh material. All that was a fascinating dance of wires and lenses and playback decks.”

To help Avnet choreograph that dance, special converters were invented just for “Up Close & Personal,” permitting the instantaneous transformation of video footage from 30 to 24 frames per second. Instead of waiting a day or two for the

video images to be converted to a speed that would read on film, the new equipment instantly adjusted the format, providing viable footage that Avnet could use immediately, to fill the myriad of monitors about the set, allowing him to simulate a “live broadcast” within the context of the film.

The news sets on which all this breakthrough technology transpired provided the visual and physical framework for Avnet to expose “The Magic Box Factor.” Scouting for what would be the exterior of WMIA, the fictional news station

that becomes Tally Atwater’s first on-air job, the filmmakers discovered that Miami’s WTVJ was actually built in the remains of an old movie theater. Production designer Jeremy Conway began his career designing sets for NBC, including the

revamped “Today Show” home, as well as David Letterman’s talk-show stage, found that an engaging metaphor.

“It was really sort of interesting, the juxtaposition of a movie theater and news because there is so much entertainment in news, so much ‘infotainment.’

The idea of the news set in a crumbly, old theater also allowed us to show the audience the difference between what it sees on television and what is behind it.

People love that, to see the lights and cameras and how it all works. So, in our WMIA set, around the desk where the anchors sit and deliver the news, we built a proscenium you’d find in an old movie house, the pin-rails and all the lights hanging from the ceiling, and constructed the control booth as though it was an extension of the old theater balcony, so the actors can go from the control room along a metal catwalk out into the theater space and down a spiral staircase, towards the news set proper and the bullpen, where all the assignment desks are.”

Conway worked closely with Avnet on the geography for this open, two-story set, strategically placing glass panels and enclosures throughout, a device that not only enabled the camera to view activity in all parts of the newsroom but also

allowed Avnet to utilize reflections. The entire set was specifically designed to capture the manic energy, the vitality and the continuous metamorphosis of images that characterize the news industry, as choreographed in an elaborate tracking

shot that follows Atwater on her first day at WMIA through the entire station, introducing her and the audience to the place and the people who will profoundly influence her life.

This tracking shot was accomplished via an ingenious combination of Steadicam and crane, one of many instances in which motion, especially through the application of the Steadicam, was employed. The idea, explains cinematographer Karl Walter Lindenlaub, is to visually describe the kinetic, capricious nature of television news.

“In the world of television news, everything is moving fast. To translate this feeling on film, Steadicam is a great tool. It gives the camera the freedom to move with the actors in a way a camera dolly could never operate. On the downside, you lose some control over your lighting, but, ideally, the energy you gain makes up for it.” Lindenlaub also made use of swiveling camera remotes, extending off the end of diving cranes and gliding dolly shots, particularly aided by the smooth surface of

the newsroom floors.

If the cast and crew had any questions about the technical aspects of the news business, they could turn to the film’s technicaF news consultant, Linda Ellman, a former NBC affiliate reporter and network field producer, and supervising producer of “Entertainment Tonight” and executive producer of “Hard Copy.”

“They brought me in as a consultant to help keep the project as authentic as possible and I’ve been available to any department that needed me. It’s been very exciting for me,” Ellman says. “It’s been a unique opportunity to see how a movie is

made, which most people in the news business never get to do.”

Among other things, Ellman, in concert with co-producer Lisa Lindstrom, worked closely with the real reporters, who appeared as extras in several scenes.

Although these reporters generally understood the scripted news event which they’d be covering, their actual reactions and lines were ad-libbed, to provide the most realistic, spontaneous background chatter as possible.

“What I would do is discuss the story they’d be covering in the movie and give them the general facts to report on,” Ellrnan explains. “I tried to include them in the process. I’d say, ‘You’ve just gotten here, this is what you know. How would you approach the story?’ Each one had his own take on the story, which was perfect.”

Lindstrom, who made sure that the reporters’ commentaries would reflect the tone of the scene and the overall storyline, notes that the journalists seemed to “get a kick out of the whole thing” and generally enjoyed the experience as much as she did.

In addition to Linda Ellman and production designer Jeremy Conway, several members of the behind-the-scenes crew also came to the film with personal experience in the TV news industry. Make-up department head Fern Buchner began her career at CBS News, working with such legendary newsmen as Harry Reasoner and Mike Wallace. Fittingly, Avnet cast her in a cameo role as WMIA’s intransigent make-up expert. Key hairstylist Alan D’Angerio worked for NBC News for many years, and still photographer Ken Regan started as a photojournalist for Time-Life. While the props department counted no alumni of the TV news industry among its members, the on-going coverage of the O.J. Simpson trial provided the perfect opportunity for prop master Tommy Tomlinson and his crew to study a broad cross section of working newscasters.

The news business is not known for its sartorial flair and the costumes proved to be some of the film’s greatest stylistic challenges. “The wardrobe for this film was very difficult; a period piece is much easier,” admits costume designer Albert Wolsky, a two-time Academy Award® winner. “The look for this was not obvious, there were many subtle nuances to it and windows in which to establish those nuances were very small. Also, each character has a humongous amount of

changes. In some ways, the Warren Justice character was easier. Jon wanted him to be relaxed, not uptight or too suited, but Tally was hard because she varies so much over time.”

It was this character arc that intrigued Wolsky, who explains that “charting Tally Atwater’s voyage of change, from her very early, unpolished look in Reno to the finale, when she becomes a seasoned, sophisticated newswoman, is what’s interesting to me.”

In Michelle Pfeiffer, Wolsky says he found a generous collaborator. “She uses clothes well, understands how they move and how they look. It’s never about ego, it’s always about if it’s right for the character.”

Wolsky remarks that he could never have achieved the artistic beats in Tally’s transformation without Pfeiffer’s partnership, especially in the case of one particularly important outfit, an alarmingly tight, hot-pink suit, “Chanel on acid, minus three or four chromosomes,” he says. The outrageous hue was by design, in concert with an overall color scheme that Wolsky, Avnet and Conway had arranged to delineate Tally Atwater’s progression in her life and in the broadcast industry.

“Jon gave us some very clear guidelines, in terms of color and look … he’s very good that way, he both anchors you down with a vision but affords you a lot of room to translate it,” Wolsky comments. “I talked with Jeremy (Conway) about it,

he’s wonderfully collaborative. Each section has its own colors, reflected in the clothes and the sets. In Miami, we used warm, rich, tropical colors; in Philadelphia, nothing but dark blues and burgundies, wintry, conservative colors. By the time

she gets to the network in New York, we’ve pared it down to even less color, grays and dark browns.”

The sets, especially the news rooms, echoed these tones as well as the material they suggested. The challenge for Conway was to create three distinct news stations that would map Tally’s evolution, from Miami’s WMIA to Philadelphia’s WFIL to the network IBS. Conway envisioned VVMIA as the neophyte Tally Atwater, hungry, ambitious newcomer, all hustle and flash, not necessarily too technologically advanced. “Some of the smaller stations don’t

even have computers,” he explains. “Paper is flying, assistants are on scanners, calling local police stations to find out what’s going on. It’s loud, bustling and very active, bursting with hot colors. WMIA is down and dirty, raw and hard, but there are a lot of inter-personal relationships and all.the incredible cultures that make up Miami.”

The network, IBS, on the other hand, “… is all about cool. It’s E-Mail and state-of-the-art communication systems. The style is calm, the goal is how collected you can be when there is breaking news, how professionally you handle the story.” To emphasize the aloof, ascetic atmosphere of IBS, in complete contrast to the manic WMIA, Conway used clean, icy tones in a “… big, simple, empty space, with a lot of blue screens. I had this idea that IBS would be just this big, curved, rear-lit blue screen. That would be the next step in ‘The Magic Box Factor.’

Instead of seeing the beat-up parts of the set, you’d see Ultimatte, a virtual news set where you can throw in any backdrop. I also thought this could be a stunning image for Tally when she finally gets to the chair she’s been coveting, only to find

this rarefied and refined set that is very isolating.”

Both Wolsky and Conway saw WAIL the Philadelphia news station where Tally Atwater stops in between Miami and the network, as the “breather after Miami, before New York,” Conway explains. “We realized that it’s better if VVFIL just neutralizes colors and textures.”

In the course of designing the sets, Conway worked with Avnet to originate the graphics and logos that are the signature of each news station. “In creating three different news stations, we also had to control the whole graphic package because that’s such a great part of the identity of any of these news stations.

Miami’s graphics will be hot and two-dimensional, put together in really quick cuts, New York will be three-dimensional, cool and saturated with pure colors, blues and blacks and WFIL will be somewhere in the middle.”

The colors, wardrobe, sets and graphics are not the only indicators of Tally’s rise towards the network. Throughout the course of the movie, her hair changes color and style, reflecting each new professional incarnation. Alan D’Angerio, who

once styled the locks of such high-powered journalists as Jane Pauley and Barbara Walters, notes that this radical and constant modification of hairdos is very common to female broadcasters. To achieve these new looks, he used approximately 6 wigs that became 8 different hair styles, an unusually high amount, he says, especially for a contemporary movie.

While this attention to the vagaries of hair may seem a small, even superficial detail, it is indicative of the different kinds of elements to which a television reporter must attend, elements that definitively separate print and broadcast journalists. Moreover, it illustrates one of Avnet’s strengths as a filmmaker.

“One of the things I’ve noticed about Jon is that he is very detail-oriented. A movie is a series of small, carefully-observed moments in which the details add up to the whole,” observes Nicksay. “What I’ve learned on this particular picture with

Jon is that each movie is made one shot at a time. Jon talks in terms of shots, he thinks of shots, he dreams shots, all day long. He told me at the beginning that his goal is for each shot to tell the entire story of the movie, which gave me a really new way of looking at the art of filmmaking, one discreet shot at a time.”

Avnet’s fascination with “the shot” is not a gratuitous, self-aggrandizing cinematic exercise but an essential, unique part of Avnet’s method of motion picture storytelling.

“Preparing for something that will be shot the following week, Jon will put himself into the moment of the characters at that time in the story and look at it from the inside out. That’s valuable to the scene because he is able to get inside it, to look at it from the inside out. He is also able to orchestrate all the different points of view that come to bear on the process of making the film. Each department is looking at the scene from its own perspective. They’re standing outside the scene, looking at it objectively. He gets inside it and forces them to come into it with him in order to determine what’s right. For me, it’s very energizing to be able to step out of the objective and into the subjective outlook,” producer Nicksay comments.

“Up Close & Personal” began shooting in Florida for about a week and two weeks in Philadelphia, prior to returning to Los Angeles. In Florida, the company visited diverse locales, from the Cuban community in Little Havana to Miami Beach’s Deco District to the island of Bahia Honda in the Florida Keys. The production spent much of its time in Philadelphia inside Holmesburg Prison, built by the Quakers in the “Elizabethan style” with a large, domed “hub” in the center, surrounded by tentacle-like hallways, lined with cells. Other Philadelphia locations included the city’s Convention Center, where the film temporarily erected a billboard emblazoned with the faces of an “Up Close & Personal” news team, including that of Stockard Channing as broadcaster Marcia McGrath. On the last day of shooting in the city, Channing’s face was replaced by Pfeiffer’s, signifying Tally Atwater’s rise in the TV news business. Philadelphians, pausing at the stoplight at the corner of the Convention Center location, watched in surprise as the crew hoisted a giant replica of Tally Atwater from the sidewalk to the scaffold.

Double-takes commenced, if they happened to look the opposite way, to see Robert Redford as Warren Justice and Michelle Pfeiffer as Tally Atwater, in front of he film crew, looking skyward to the same billboard. Upon returning to Los Angeles, the production spent several days in the downtown area. Some locations included the elegant Biltmore Hotel, the site of the 1937 Academy Award® ceremonies and, legend has it, the place in which the statuette that would be called Oscar was designed, as well as the sprawling neighborhood beneath Dodger Stadium, which doubled for the Philadelphia housing projects. The atch the proceedings there were treated to the first summer snowfall in Los Angeles, albeit one made of soap suds provided by the special effects team. These intrepid weathermen also created a midnight rain in the high desert of California, in a trailer park that doubled for the Reno home of Luanne Atwater. Giant 12-K lights glared down on the set, illuminating the night sky as they back-lit the downpour that soaked the cast and crew, who had been warned to wear their rain gear for this scene. Fittingly, the site of this cinematic storm was called The Oasis Trailer Park.

ABOUT THE CAST

ROBERT REDFORD (Warren Justice) has won widespread acclaim for his work, both as an actor and a filmmaker. His direction of the searing family drama “Ordinary People” earned him an Academy Award® for Best Director and he recently garnered an Oscar nomination for his direction of “Quiz Show.”

Born in Santa Monica, California, Redford attended the University of Colorado, only to leave school after two years to study art in Paris and Florence.

He continued to pursue art upon his return to the States, attending the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. At the suggestion of an instructor, he enrolled in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where a passion for acting superseded his interest in art.

His career blossomed in Manhattan, where a small part on Broadway led to roles in several of the major New York-produced live television dramas. His performances in a Playhouse 90 presentation of “In The Presence of Mine Enemies” and Sidney Lumet’s production of Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Conneth” won him critical recognition. He went on to appear in the Broadway production of “Little Moon of Alban” with Julie Harris and, in 1961 he made his feature film debut in “War Hunt.” Later that year, he starred in his first Broadway show, “Sunday in New York,” followed by a starring role opposite Elizabeth Ashley in Neil Simon’s “Barefoot in the Park.”

It was Redford’s teaming with Jane Fonda in the film version of “Barefoot in the Park” that earned him acclaim in this medium. Films that followed included “Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here,” “Little Fauss and Big Halsey” and “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” opposite Paul Newman, which established him as a star.

Redford went on to embody an array of characters in a spectrum of films, many from his own production company, Wildwood Enterprises, which he founded in 1968. Under the Wildwood banner, Redford starred in and produced “Downhill Racer,” a film that examined competition and an obsession with winning, as well as “The Candidate,” a probing examination of the effect of a campaign on a political candidate. In 1976, Redford developed, produced and starred with Dustin Hoffman in “All the President’s Men,” the cinematic telling of the Watergate scandal, as uncovered by Washington Post journalists Woodward and Bernstein.

Other film roles include the mountain man “Jeremiah Johnson,” one of Redford’s personal favorites, “The Way We Were,” opposite Barbra Streisand, “The Sting,” for which he received an Oscar nomination; “The Great Gatsby,” “Three Days of the Condor,” “The Electric Horseman,” which reunited him with Jane Fonda, “Brubaker,” a baseball player in “The Natural,” “Out of Africa,” opposite Meryl Streep; the leader of a high-tech spy ring in “Sneakers,” and the ultimate gambler in “Indecent Proposal,” with Demi Moore.

Behind the camera, Redford executive produced and narrated a documentary about the controversial conviction of native American Leonard Peltier for allegedly killing two FBI agents on the Pine Ridge Reservation, which was released by Miramax in 1992. That same year, Columbia Pictures released “A River Runs Through It,” which Redford produced and directed. Based on the novella by Norman Maclean, the film starred Tom Skerritt, Brad Pitt, Craig Sheffer and Emily Lloyd. In 1987, Redford also produced and directed “The Milagro Beanfield War.”

An advocate of independent filmmaking, Redford founded the Sundance Institute in 1980, an organization “dedicated to the support and development of emerging screenwriters and directors of vision and to the national and international exhibition of new American independent cinema … His interest in nature and conservation also led him to found the Institute for Resource Management, to create a forum for discussion between developers and environmentalists.

MICHELLE PFEIFFER (Tally Atwater) is one of the screen’s most appealing and highly regarded artists. Her roles have run the gamut, from an affected actress in ”Sweet Liberty” to a Soviet woman caught up in espionage in “The Russia House.” She has earned Oscar nominations for her performances in “Dangerous Liaisons,” in which she played an ingenue trapped in a Machiavellian game of love and power; “The Fabulous Baker Boys,” where she portrayed a tough, feisty, sexy singer and “Love Field,” as a sheltered woman from the rural South in the early 60s whose interest in Jackie Kennedy takes her on a journey that profoundly changes her life.

Born in Santa Ana, California, Pfeiffer moved to Los Angeles to study and pursue a career in acting. After appearing in featured roles on television and in several films, Pfeiffer turned in a notable performance as of one of a troika of frustrated suburban women turned lusty sorceresses in “The Witches of Eastwick,” opposite Jack Nicholson, Susan Sarandon and Cher, which earned her broad praise and international attention. She rapidly became known as one of Hollywood’s most facile leading talents, a deft comedienne, a consummate dramatic actress, an impressive vocalist, as demonstrated by her steamy rendition of “Makin’ Whoopee” atop a piano in “The Fabulous Baker Boys.” Her bravura turn as a Mafia moll in “Married to the Mob” and her darkly funny incarnation of Batman’s feline nemesis in “Batman Returns” illustrated her considerable comedic gifts, while her subtle portrayal of a scandalously independent woman in the late 1800s in Martin Scorsese’s “Age of Innocence” won her the approval of audiences and critics alike. Other film credits include “Scarface” and “Frankie and Johnny,” opposite Al Pacino; “Tequila Sunrise,” with Kurt Russell and Mel Gibson, and a mesmerizing performance in Mike Nichols’ modern werewolf tale, “Wolf.” This past year, Pfeiffer starred as a compassionate, headstrong teacher in Hollywood Pictures’ hit “Dangerous Minds.”

STOCKARD CHANNING (Marcia McGrath) divides her acting time between the stage and screen. She recently received critical praise on Broadway for her bravura performance in Tom Stoppard’s spy drama “Hapgood” and garnered an Oscar nomination for Best Actress for her portrayal of Ouisa Kittredge, a wealthy, New York socialite in Fred Schepisi’s film version of John Guare’s play, “Six Degrees of Separation,” a role she originated on Broadway, earning a Tony nomination and an Olivier Award when she reprised the role at London’s Royal Court Theatre. Prior to joining the cast of “Up Close & Personal,” Channing completed work on the upcoming feature “Moll Flanders,” based on the classic novel, which filmed on locations in Ireland.

Channing began her career on the stage, winning a Tony Award in 1985 for her performance in “Joe Egg,” which also brought her nominations for a Drama Desk Award and the Outer Critic’s Circle Award. Her work in John Guare’s “House of Blue Leaves” earned her another Tony Award nomination. She won a Drama Desk Award for her off-Broadway role in “Woman In Mind.” Channing also starred in another John Guare play, “Four Baboons Adoring the Sun,” at Lincoln Center.

Her other Broadway shows include “They’re Playing Our Song,” “The Rink,” “The Golden Age” and “Two Gentlemen of Verona,” as well as the off-Broadway productions of “Lady and the Clarinet,” “The Homecoming,” “Absurd Person Singular,” “As You Like It” and “Love Letters.”

Channing’s role in Mike Nichols’ film “The Fortune,” with Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty, introduced her to moviegoers. She followed that with the hit movie musical “Grease,” and her memorable portrayal of the tough, rebellious Rizzo became the definitive interpretation of the character for critics and audiences alike.

Later, she reteamed with Nichols and Nicholson in “Heartburn,” also starring MerylStreep. Other diverse film credits include “Without a Trace,” “The Cheap Detective,” “Sweet Revenge,” “The Big Bus,” “A Time of Destiny,” “Staying Together,” “Meet The Applegates,” and “Married To It,” among others.

On television, Channing has three times been honored with Emmy Award nominations, the first for the CBS miniseries “Echoes in the Darkness,” the HBO film “Perfect Witness” and the CBS telefilm “David’s Mother.” In 1988, she won the CableACE Award for her work in “Tidy Endings.” Other television credits include the Hallmark Hall of Fame presentation of “The Room Upstairs,” and “The Girl Most Likely To …”

JOE MANTEGNA (Bucky Terranova) is a versatile actor, known for his work on the stage as well as the screen. A Chicago native, Mantegna studied at the Goodman School of Drama, and, subsequently, he joined the city’s famed theater ensemble, the Organic Theatre Company, with which he twice toured Europe. Upon his return, he joined the Goodman Theatre and began what would become a long association with playwright-director David Mamet. This alliance led to a Joseph Jefferson Award and a Tony Award for his acclaimed Broadway performance as Richard Roma in Mamet’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, “Glengarry Glen Ross.” He subsequently starred on Broadway as Bobby Gould in Mamet’s “Speed The Plow.”

Mantegna made his Broadway debut in Stephen Schwartz’s musical of Studs Terkel’s “Working.” Off-Broadway, Mantegna conceived and co-wrote the play “Bleacher Bums.” He won an Emmy Award for the subsequent television production of that play.

Mantegna made his feature film bow in “Compromising Positions” and went on to appear in such films as “The Money Pit,” “Weeds” and “Suspect.” He starred opposite Lindsay Crouse in the critically lauded David Mamet film “House of Games” and also starred in Mamet’s movies, “Things Change,” for which he received the Best Actor Award at the Venice Film Festival, and the dark police thriller “Homicide.” Other films in which Mantegna starred include John Schlesinger’s “Eye For An Eye,” Billy Crystal’s “Forget Paris,” Woody Allen’s “Alice,” Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather Ill,” Barry Levinson’s “Bugsy,” and Steven Zaillian’s “Searching for Bobby Fischer,” as well as “Baby’s Day Out,” “Queen’s Logic,” “Wait Until Spring Bandini” and “Family Prayers.” Mantegna’s upcoming films include Stephen King’s “Thinner” for Paramount, Miramax’s “Albino Alligator,” and Keystone’s “Underworld.”

On television, Mantegna starred in the HBO movies “State of Emergency” and “Comrades of Summer,” along with the TNT Special Presentation of David Mamet’s “The Water Engine” and the crime anthology, “Fallen Angels.” He served as narrator of the Oscar-nominated documentaries “Crack U.S.A, County Under Siege” and “Death on the Job.” He also directed a critically praised stage production of David Mamet’s “Lakeboat,” which enjoyed a long run in Los Angeles.

KATE NELLIGAN (Joanna Kennelly), a multi-talented, highly regarded actress, earned the attention of critics and audiences for her riveting portrayal of a conflicted southern mother in Barbra Streisand’s “The Prince of Tides,” for which she received an Academy Award® nomination for Best Supporting Actress. The Canadian-born Nelligan began her career on the London stage. A member of the National Theatre of Great Britain, she appeared in productions that includ “Heartbreak House,” directed by John Schlesinger and “Tales From the Vienna Woods,” directed by Maximillian Schell. She was also a member of the prestigious Royal Shakespeare Company, with which she appeared as Rosalind in “As You Like It,” among other roles. Nelligan made her West End debut in David Hare’s “Knuckle,” for which she won the London Critics’ Most Promising Actress Award. She went on to star as Susan Traherne in Hare’s play “Plenty,” for which she won the London Critics’ Best Actress Award. She recreated that role at New York’s Public Theatre and on Broadway, for which she received a Tony Award nomination. Nelligan earned another Tony Award nomination the following year for her work in “Moon For the Misbegotten,” received a third Tony nomination for her work in the Broadway production of “Serious Money” and a fourth for “Spoils of War,” as performed at the Second Stage on Broadway.

On film, Nelligan appeared in Garry Marshall’s “Frankie and Johnny,” which first teamed her with Michelle Pfeiffer. Nelligan’s performance in that feature earned her the D.W. Griffith Award from the National Board of Review and a British Academy Award. She appeared in Mike Nichols’ “Wolf,” which also starred Pfeiffer.

Other movie credits include Woody Allen’s “Shadows and Fog,” Carl Reiner’s “Fatal Instinct,” Jocelyn Moorehouse’s “How To Make An American Quilt,” as well as “Dracula,” “Eye of the Needle,” “Without A Trace,” “Eleni” and “White Room.”

She can currently be seen in Mort Ransen’s “Margaret’s Museum,” for which she received a Genie Award for Best Supporting Actress opposite Helena Bonham Carter and Kenneth Welsh.

Nelligan was nominated for an Emmy Award for her role in The Disney Channel’s “Avonlea,” for which she won a Gemini Award. She won another Gemini for her performance in the USA movie “Diamond Fleece,” in which she starred opposite Ben Cross and Brian Dennehy. Nelligan also appeared in such television movies as “Liar, Liar,” for CBC/CBS, NBC’s “Shattered Trust: The Shari Karney Story,” with Melissa Gilbert and Ellen Burstyn, and the CBS movie-of-the- week ‘The James Mink Story,” opposite Louis Gossett Jr. She also revived her Tony Award nominated role of Elise in “Spoils of War” for ABC and appeared in the CBS miniseries “Million Dollar Babies,” opposite Beau Bridges.

GLENN PLUMMER (Ned) captured the attention of audiences in the boxoffice hit “Speed.” Since then, Plummer has starred in the features, “Strange Days,” Kathryn Bigelow’s futuristic thriller, and Paul Verhoeven’s provocative musical/drama “Showgirls.” He will soon be seen in MGM’s “The Substitute” with Tom Berenger.

Born in Richmond, California, Plummer has won critical praise for his performances in films such as “Pastime,” a baseball fable that won the Audience Award for Dramatic Films at the 1991 Sundance Film Festival, as well as “South Central,” the story of a gang member and young father who finds his way in prison, a film on which he also served as creative consultant. Other film credits include “Frankie and Johnny,” where he first worked with Michelle Pfeiffer; “Colors,” “Menace II Society,” “Funny Farm,” ‘Trespass” and his first film, “Who’s That Girl?”

On television, Plummer has appeared on such shows as “Equal Justice,” “L.A. Law” and “China Beach,” as well as the miniseries “Hands of a Stranger,” the television movies “Murderous Vision,” “Hearts of Stone,” “The Father Clements Story” and “Tour of Duty.” Plummer also starred in the acclaimed TNT production, “Heat Wave,” a drama about the Watts riots, executive produced by Jon Avnet.

Plummer studied acting at Diablo Valley College, Contra Costa College and San Francisco State prior to moving to Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, he appeared in several stage productions, including “The Task,” “Palladium Is Moving,” “Better

Living” and “Three Ways Home.”

JAMES REBHORN‘s (John Merino) feature film credits include the upcoming “Independence Day” and “If Lucy Fell,” as well as “White Squall,” “How To Make An American Quilt,” “I Love Trouble,” “Guarding Tess,” “Carlito’s Way,”

“Scent of a Woman,” “Lorenzo’s Oil,” “Blank Check,” “8 Seconds,” “My Cousin Vinny,” “White Sands,” “Silkwood,” “Cat’s Eye,” “Regarding Henry” and “Basic Instinct.”

Born in Philadelphia, Rebhorn earned his BA from Wittenburg University and his MFA from Columbia University before starting his career. He played Doc Gibbs in the Tony Award winning revival of “Our Town” and received a Dramalogue Award for his performance in the La Jolla Playhouse production of “Nebraska.”

Most recently he was praised by New York critics for his work in Ron Nyswaner’s play “Oblivion Postponed” as Kyle, the role he created in the original production at the Bay Street Theatre in Sag Harbor.

On television, Rebhorn has appeared in recurring roles on “The Guiding Light” and “As the World Turns,” and lead roles on “Law and Order,” “The Wright Verdicts,” “Under Fire,” “I’ll Fly Away,” “Sarah, Plain and Tall,” “Spencer for Hire,” “Kate and Allie,” “Against the Law,” and “JFK: Reckless Youth.”

SCOTT BRYCE (Rob Sullivan) previously appeared in the feature film “Lethal Weapon Ill,” directed by Richard Donner. He also starred in and co-wrote “T.V. Dad,” for the A&E Network.

After attending The Juilliard School, Bryce began his career with roles in numerous New York and regional theatre productions including “Caesar and Cleopatra” on Broadway with Rex Harrison and Elizabeth Ashley; as well as off-Broadway’s “Sally’s Gone She Left Her Name.” His other stage credits include “Comedy of Errors,” “Hobson’s Choice,” “The Glass Menagerie,” “The Ronde,” “The Subject Was Roses,” and “The Bible on Broadway.”

Bryce’s long list of television credits includes guest starring roles on “Something Wilder,” “Hope and Gloria,” “Matlock,” and ‘The Commish.” He received two Emmy Award nominations for his work on the daytime drama “As the World Turns,” and was a series regular on “2000 Malibu Road” and “Facts of Life.”

He also enjoyed recurring roles on “LA. Law” and “Murphy Brown,” and has appeared in such movies-of-the-week as The Calling” for NBC, “Love You to Death” for CBS, and “Exclusive” for ABC.

RAYMOND CRUZ (Fernando Butlanda) has starred in a wide variety of motion pictures, television and theatre productions. Among his more prominent feature film credits are Walt Disney Pictures’ live-action comedy adventure “Operation Dumbo Drop,” as well as “Clear and Present Danger,” “Dragstrip Girl,” “Dead Badge,” “Bound by Honor” and “Under Siege.” He will soon be seen in “Broken Arrow,” “The Substitute” and ‘The Rock.”

On television Cruz has stared or guest starred on such hits as “NYPD Blue,” “Walker Texas Ranger,” “The Marshal,” ‘Working and Living in Space,” “Murder,She Wrote,” “Vietnam War Stories,” “Gangs,” “Hunter,” “Life Stories,” “Matlock,” and “A Year in the Life.”

Cruz won the 1989 Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award for his dual portrayals of Mr. Goglas and Vincente in “Buck,” at the Heliotrope Theatre. He also appeared on stare in “4-H Club,” “American Buffalo,” and “Short Eyes.”

DEDEE PFEIFFER (Luanne Atwater) delights audiences on the CBS Golden Globe Award winning Best Comedy series “Cybill,” (which has also been nominated for a Screen Actors Award for Best Ensemble Cast), as the very funny Rachel Blanders. Other television credits include guest starring roles on HBO’s celebrated series “Dream On,” the hit NBC comedies “Seinfeld” and “Wings.” She also co-starred in the movie-of-the-week “Tough Love,” opposite Lee Remick, Bruce Dern, Piper Laurie and Jason Patric.

Pfeiffer’s films include “Vamp,” with Grace Jones, Jon Amiel’s “Tune In Tomorrow,” Gregory Nava’s acclaimed family saga “Mi Familia,” Claudia Hoover’s “Double Exposure” and a memorable role in the hit “Falling Down,” as the fast-food cashier who refuses to serve breakfast one minute past the hour. She will soon be seen starring with George Clooney in the feature “Red Surf.”

Born in Orange County, California, she starred in numerous stage plays including “My Rebel” at the Lex in Hollywood, and “Strains of Affection” at the Court Theatre in Los Angeles. Additional stage credits include “Trilogy of One Acts By Margo Kessler” at the Coast Playhouse and “A Quality of Life” at the Tiffany, both in Los Angeles.

MIGUEL SANDOVAL (Dan Duarte) has enjoyed starring roles in a long list of feature films and television productions. Among his more prominent motion picture credits are “Get Shorty,” “Clear and Present Danger,” “Jurassic Park,” “White Sands,” “Jungle Fever,” “Do The Right Thing,” “Sid and Nancy,” “Repo Man,” and the upcoming “Mrs. Winterbourne.”

His equally impressive list of made-for-television movies includes “Red Wind,” “Texas,” “The Cisco Kid,” “El Diablo,” “Nothing Personal,” and “Majority Rule.” A representative listing of his episodic television credits includes “Murder One,” “Home Improvement,” “NYPD Blue,” “The Marshal,” the BBC series “Birds of a Feather,” “Green Dolphin Street,” and “L.A. Law.”

For the past two decades, NOBLE WILLINGHAM (Buford Sells) has appeared in a long list of feature films, made-for-television movies and series. A partial list of his diverse motion picture credits include “Ace Ventura,” “Guarding Tess,” “The Distinguished Gentleman,” “Of Mice and Men,” “City Slickers” and “City Slickers II,” “Good Morning, Vietnam,” “The Howling,” “Blind Fury,” “The First Monday in October,” “Norma Rae,” “Brubaker,” “China Town,” “Butch and Sundance,” “The Last Picture Show,” and “Independence Day” (1983).

Television audiences have enjoyed Willingham’s performances guest-starring on such episodics and sitcoms as ‘Tales From the Crypt,” “Northern Exposure,” “Home Improvement,” “Quantum Leap,” and “Murder, She Wrote,” among others. His miniseries and movies-of-the-week include “Woman With a Past,” “Faithless,” “Unconquered,” “The Alamo,” “The Gambler,” “The Blue and the Gray,” “Dream West,” “Night Train to Terror’ and “Backstairs at the White House.”

Willingham has also been a series regular on “Walker – Texas Ranger,” “The Ann Jillian Show,” “Black Bart,” “After M*A*S*H,” and “The Protectors,” among many others.

ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS

JON AVNET (Produced/Director) has helmed many critical and boxoffice successes, ranging from the hugely popular comedy “Risky Business,” which he produced, to the Oscar-nominated, sleeper hit, “Fried Green Tomatoes,” which he produced and directed.

Born in Brooklyn, Avnet graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a degree in Film and Theater Arts. After directing several off off-Broadway productions and working at La Mama, he was awarded a directing fellowship at the

American Film Institute. Upon completing his studies there, he started his first production company, partnered with Steve Tisch.

Avnet began his career as a producer. “I knew temperamentally, I would never make it as a director for hire, so I hoped I could learn to produce and then when I could create an opportunity to direct for myself I would have enormous control. It worked out very well in that respect.” Among Avnet’s television productions is the highly praised docu-drama about domestic violence, “The Burning Bed,” starring Farrah Fawcett, which garnered eight Emmy nominations and is still the highest rated MOW ever aired on NBC. Avnet also produced the critically acclaimed ABC series “Call to Glory” which introduced Elisabeth Shue, currently in “Leaving Las Vegas,” as well as the TNT movie “Heat Wave,” the story of the Watt’s Riots, which won four CableACE Awards, including Best Picture of the Year.

Avnet segued from producing to directing. He began with several episodes of “Call To Glory” and directed and co-wrote his first and only telefilm, “Between Two Women,” starring Colleen Dewhurst and Farrah Fawcett. Dewhurst’s performance in the TV movie won her a Best Actress Emmy Award.

In 1986, Avnet formed a new partnership with Jordan Kerner. Among their feature credits are the screen interpretation of Bret Easton Ellis’ nihilistic novel “Less Than Zero,” starring Robert Downey, Jr. as the film’s antihero; “Men Don’t Leave,” starring Jessica Lange, Chris O’Donnell and Charlie Korsmo, and “Miami Rhapsody,” starring Mia Farrow, Sarah Jessica Parker and Antonio Banderas, which they executive produced. Avnet/Kerner also produced “Fried GreenTomatoes,” starring Jessica Tandy, Kathy Bates, Mary Stuart Masterson, Mary-Louise Parker, Chris O’Donnell and Cicely Tyson, which marked Avnet’s debut as a film director and earned three Academy Award® nominations. He went on to direct the coming-of-age drama “The War,” starring Kevin Costner and Elijah Wood.

DAVID NICKSAY (Producer) has been behind a host of films, in various capacities, from independent producer to studio production executive to executive producer. As the latter, he piloted such recent films as the witty second installment of the life and times of the Addams family, “Addams Family Values” and the boxoffice hit “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves.” Other film credits include the suspense drama “Pacific Heights,” the thriller “White Sands,” the western “Young Guns II,” as well as “Stay Tuned” and “Freejack.” As an independent producer, Nicksay’s credits include the critically acclaimed, coming-of-age story “Lucas,” and “Mrs. Soffel,” starring Mel Gibson and Diane Keaton.

Nicksay’s television credits as a producer include the two-hour pilot of the well-regarded. series “Call To Glory” and the Emmy-nominated NBC mini-series “Little Gloria … Happy at Last.”

Born in Massachusetts, Nicksay attended Hampshire College as a performing arts major. He began his career in Hollywood as part of the Directors Guild Training Program, then became an independent producer. In 1986, Nicksay joined Paramount Pictures as vice president of production and the following year, he became senior vice president of production. During his tenure there, Nicksay oversaw a diverse slate of projects, including “Scrooged,” “Coming To America,” “Ghost,” “The Two Jakes,” “The Untouchables” and “Star Trek V: The Final Frontier.” In 1989, he joined Morgan Creek Productions as president and head of production.

JORDAN KERNER (Producer) most recently, with Jon Avnet, produced Touchstone Pictures’ romantic comedy “Miami Rhapsody,” as well as Walt Disney Pictures’ live-action comedy “D2: The Mighty Ducks.” He also executive produced Disney’s comedy/adventure hit “The Three Musketeers,” as well as the made-for- television movies “For Their Own Good” and “The Switch.” They also produced the original “The Mighty Ducks” comedy, as well as the upcoming “Mighty Ducks III.”

Prior to that, Mr. Kerner produced the critically acclaimed “Fried Green Tomatoes,” featuring Academy Award-winning actresses Jessica Tandy and Kathy Bates. In addition he and Mr. Avnet produced Touchstone Pictures’ “When a Man Loves a Woman,” starring Andy Garcia and Meg Ryan, as well as “The War,” starring Kevin Costner, which Mr. Avnet also directed.

Mr. Kerner comes from a background in law as well as television production, holding positions in each area before his appointment as vice president of dramatic series development for ABC Entertainment. There, he brought such series as “Moonlighting” and “Call to Glory” to the network before joining with Jon Avnet to produce the multiple Emmy and ACE Award-winning “Heat Wave,” the multiple Emmy Award-winning “Do You Know the Muffin Man?” “Nightman,” “My First Love” and “Side By Side,” among others. He also produced the telefilms “For Their Own

Good,” “The Switch” and “Backfield in Motion,” starring Roseanne and Tom Arnold.

The Avnet/Kerner Company’s first production was the motion picture “Less Than Zero.”

JOAN DIDION & JOHN GREGORY DUNNE (Written by) are renowned novelists, essayists and screenwriters. Didion’s acclaimed non-fiction works include Slouching Towards Bethlehem, The White Album, Salvador, Miami and After Henry. Her novels include Play It As It Lays, A Book of Common Prayer, Democracy and The Last Thing He Wanted, which will be published by Alfred Knopf in October. Dunne’s respected novels include Vegas, True Confessions, Dutch Shea. Jr., The Red. White and Blue and Playland. His works of non-fiction include Delano, The Studio, Ham and Incident in Los Angeles, which chronicled the Rodney King incident in Los Angeles and the subsequent trial of the four police officers accused of assaulting him. As screenwriters, the Dunnes have penned “The Panic In Needle Park,” “Hills Like White Elephants,” “A Star Is Born” (with Frank Pierson), starring Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson, and “Broken Trust,” starring Tom Selleck, which aired on TNT, along with screenplay adaptations of their books “Play It As It Lays” and “True Confessions,” among others. Didion occasionally contributes to such publications as the The New York Review of Books and The New Yorker, for which Dunne also regularly writes. Didion and Dunne reside in Manhattan.

ED HOOKSTRATTEN (Executive Producer) has been an important figure in television news, as lawyer and agent to many of the industry’s most respected reporters and anchors, as well as a major influence on television in general.

A graduate of the University of Southern California, Hookstratten earned his J.D. at Southwestern University School of Law. As a lawyer, he gravitated to the world of entertainment and in the late 1960s, early 1970s, Hookstratten represented many of television’s most popular entertainers: Rowan and Martin, the Smothers Brothers, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop, Glen Campbell and Elvis Presley.

Hookstratten helped bring the syndicated comic strip “Peanuts” to the air, thus creating a television tradition as well as inaugurating the prime-time animated special. He combined his legal experience with his knowledge of television and

began to represent reporters and anchors, as well as entertainers. Some of his clients include Tom Brokaw, Bryant Gumbel, Tom Snyder and Johnny Carson.

A resident of Los Angeles, Hookstratten is an active citizen. He has served as commissioner of the State of California’s Motion Picture Council, commissioner, as well as vice president of the Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreation, commissioner, as well as vice president of the Los Angeles Department of Utilities and Transportation, commissioner of the Los Angeles Board of Administration Retirement System, director of the Los Angeles Police Memorial Foundation and has been a member of the Crime Prevention Advisory Council of the Los Angeles Police Department, among many other associations. He has been a member of the Southwestern University Board of Trustees since 1984 and is a lifetime member of USC Associates. In 1984, he received the Distinguished Citizen Award from the city of Los Angeles.

One of the motion picture industry’s legendary producers and executives, JOHN FOREMAN (Executive Producer) co-founded Creative Management Agency in the 1960s (which later became ICM), before making his feature film producing debut with the classic “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” He received his first Academy Award® nomination for that film and subsequently served as producer or executive producer on a long list of hits including, “They Might be Giants,” “Sometimes a Great Notion,” ‘The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man- in-the-Moon Marigolds,” “Pocket Money,” “The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean,” “The Mackintosh Man,” “The Man Who Would Be King,” “Bobby Deerfield,” “The Great Train Robbery,” “The Ice Pirates,” “Prizzi’s Honor” (Oscar nomination).

In 1982, Foreman was named vice president of worldwide theatrical production for MGM/UA. In 1988, again independent, he asked the writers Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne to write the screenplay for “Up Close & Personal,” and worked with the Dunnes on the script until his sudden death in 1992.

KARL WALTER LINDENLAUB, B.V.K. (Director of Photography) shot the epic romance “Rob Roy,” directed by Michael Caton-Jones, starring Liam Neeson as the legendary Scotsman and Jessica Lange. Prior to that, he served as cinematographer on the sci-fi adventure hit “Stargate,” directed by Roland Emmerich, starring Kurt Russell, James Spader and Jaye Davidson. “Stargate” marked Lindenlaub’s third collaboration with Emmerich, having also worked on the director’s “Universal Soldier” and “Moon 44,” for which Lindenlaub won the German Film Award for Best Cinematographer. Lindenlaub’s additional credits include “CB4,” the German film “Polsky Crash” and “Last of the Dogmen.”

The Hamburg native graduated from the Munich Film and Television School in England. He returned to Germany and made his feature debut on “Tango in the Belly,” and went on to film “Ghost Chase,” Ute Wieland’s “The Year of the Turtle,” and “Eye of the Storm,” his first feature in America. Lindenlaub reunited with Roland Emmerich on the soon-to-be-released sci-fi adventure “Independence Day.”

JEREMY CONWAY (Production Designer) previously worked with director/producer Jon Avnet on “The War” as the film’s art director. Other features on which he served in that capacity include “Sabrina,” starring Harrison Ford, directed by Sydney Pollack; “The Super,” starring Joe Pesci; Adrian Lyne’s psychological thriller “Jacob’s Ladder” and “Crocodile Dundee II,” among others.

He was the New York art director on Oliver Stone’s “The Doors,” assistant art director on “Scenes From a Mall” and on Alan Parker’s dark mystery “Angel Heart.”

Conway began his career in the theater, designing for many regional theaters and opera companies. He then spent many years with NBC, designing a broad swath of news and entertainment shows including “Late Night With David Letterman,” the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, Penn and Teller’s “Don’t Try

This At Home” and the new “Today” show studios on the street level of Rockefeller Plaza in Manhattan. Other production design credits include the miniseries “Stephen King’s Golden Years” for CBS and ‘The Original Max Talking Headroom Show” for HBO.

Conway has received three Emmy Awards and a CableACE Award for his work. A resident of Manhattan, Conway makes his feature debut as production designer on “Up Close & Personal.”

DEBRA NEIL-FISHER (Edited by) has collaborated with Jon Avnet on several pictures, including “The War,” “Fried Green Tomatoes” and the made-for- television films “Breaking Point” and “Heat Wave,” the latter winning four CableACE Awards, including Best Editing for Neil-Fisher. Other credits include the cable film “Memphis,” several television movies, including “The Hillside Strangler,” “One More Time,” “Face of Love” and “The Amy Fisher Story.” She also served as editor on the Academy Award®-winning short “Ray’s Male Heterosexual Dance Hall.”

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Neil attended the University of Southern California’s film school.

ALBERT WOLSKY (Costume Designer) has won two Academy Awards®, for “All That Jazz” and “Bugsy,” and has received Oscar nominations for his work on the epic drama “Sophie’s Choice,” starring Meryl Streep; the coming-of-age story “The Journey of Natty Gann,” and the visually stunning fable ‘Toys.”

Other film credits include the soon-to-be-released “Striptease” and “The Grass Harp,” as well as “Junior,” “The Pelican Brief,” “Enemies, A Love Story,” “Down and Out in Beverly Hills,” “The Turning Point,” “Lenny,” “Grease” and “Manhattan.”

LISA LINDSTROM (Co-Producer) serves as senior vice president of feature film development and production for the Avnet/Kerner Company, where she has been involved in the creation of numerous film and television projects. One of her first successes for Avnet/Kemer was the hit film “Fried Green Tomatoes,” which, as co-producer, she helped nurture from development through production. Most recently, she co-produced “The War.”

Among her other favorite projects are Avnet/Kerner’s upcoming miniseries about Nelson Mandela called “Apartheid” and the TNT film “Heat Wave,” which won a Best Picture CableACE Award for its portrayal of the Watts uprising. Prior to joining Avnet/Kerner, she was story editor for filmmaker Alan J. Pakula and worked on his films “Dream Lover” and “Orphans.”

Her extensive theater background includes work in New York at the Ensemble Studio Theater, La Mama, the Circle Repertory Company and New Dramatists. In Los Angeles, she has been active as a director and dramaturg with the Playwright’s Unit and the Women’s Artist Group at the Los Angeles Theater Center.

A graduate of Sarah Lawrence College, Lindstrom holds a Masters of Fine Arts in Directing from Carnegie-Mellon University.

MARTIN HUBERTY (Co-Producer) co-produced “The War,” “The Mighty Ducks,” and “Fried Green Tomatoes.” Huberty has served in various production capacities at Avnet/Kerner for the past eight years, including associate producer of the acclaimed telefilms “Breaking Point” and “Heatwave.” Born and raised in Northern California, Huberty completed his studies in England before receiving a degree in international relations from the University of California at Davis.

THOMAS NEWMAN (Music by) recently received Academy Award® nominations for his work on “The Shawshank Redemption” and “Little Women.”

His other credits include “How to Make an American Quilt,” “Unstrung Heroes,” “the Player,” “The War,” “Flesh and Bone,” “Scent of a Woman,” “Fried Green Tomatoes,” “Men Don’t Leave,” “Deceived,” “Desperately Seeking Susan.” For television he composed the scores for HBO’s “Citizen Cohn,” as well as TNT’s “Heat Wave,” among others. He also received a Grammy Award nomination for “The Shawshank Redemption.”

Born in Los Angeles, Newman is a member of one or America’s most noted musical families. His father was the acclaimed film music composer Alfred Newman, his uncles were Lionel and Emil Newman and his cousin is songwriter Randy Newman. Thomas attended Yale University, where he received his Master’s degree in music.